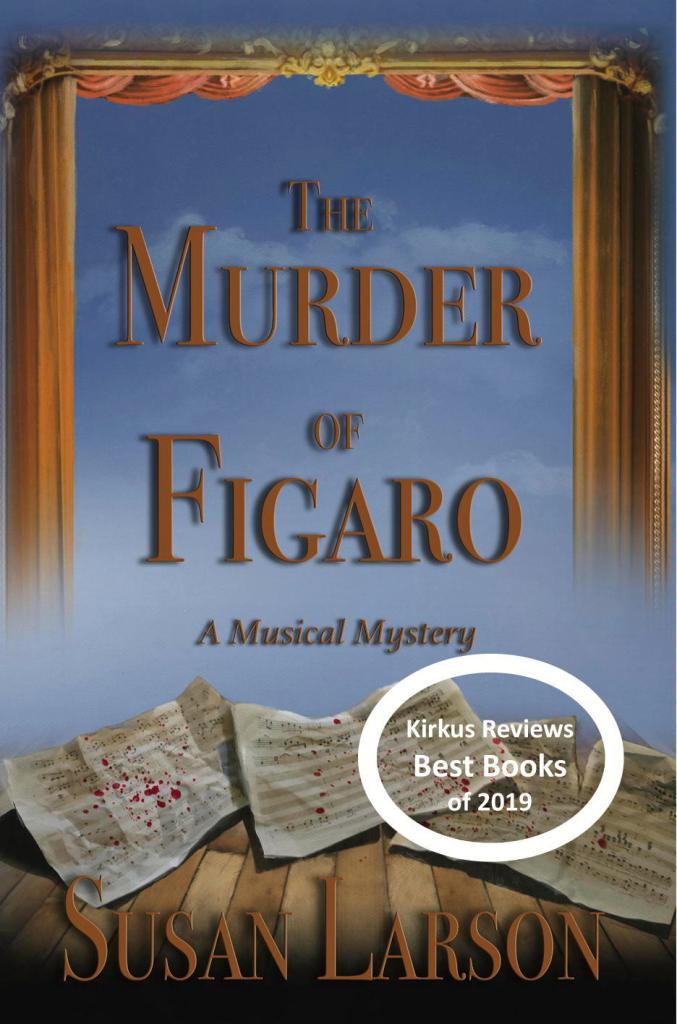

Here is another feature about the historical characters who appear in my comic novel “The Murder of Figaro.” Just the bald facts, no fiction in this story. My book is available on Amazon.com, Barnes&Noble and your favorite e-book platform.

Mozart’s wife and three sisters-in-law were all trained sopranos. Their father, Franz Fridolin Weber, was, by several accounts, a contrabass player, a singer, a prompter in the theater and a music copyist, first working in Mannheim, Germany, then moving his family twice to follow his eldest daughter’s engagements; first to Munich, and finally to Vienna.

The eldest sister, Aloysia, enjoyed a significant international career; the second eldest, Josepha was a noted singer who created the role of the Queen of the Night in “The Magic Flute”. Constanze, married to Mozart, never worked as a professional singer, although she sang the difficult solos in her husband’s Great Mass in C minor in Salzburg in 1783. The youngest sister, Sophie, sang a few seasons at the Burgtheater in Vienna.

Mozart flirted with all the Weber sisters, but Aloysia was his first official crush. He loved her singing and her incredible range, and wrote five concert arias (including Popolo di Tessaglia, which features a high G6). Aloysia appeared in Mozart’s Operas as Madame Herz, Konstanze, Donna Anna and Sesto, in spite of having icily refused his offer of marriage. The sensitive Mozart, deeply wounded, was purported to have said, or sung: “Whoever doesn’t want me can kiss my ass.” And married Constanze instead.

Josepha also had stratospheric in Alt notes, but was only required to ascend to a mere F6 when she sang the Vengeance aria as the Queen of the Night. She was the long- reigning prima donna at Theater an der Wien. She married twice, retired and lived her entire adult life in Vienna.

Constanze settled down to domestic duties and the production of many Mozart offspring (only two of whom survived to adulthood), singing as a gifted amateur, and encouraging her husband to write Baroque counterpoint, for which she had a particular liking.

Sophie, the baby of the family, was described by Mozart as “feather-brained,” is now famous for her heart-rending descriptions of the composer’s last days: how she and Constanze sewed him a quilted bed jacket that could be put on from the front, because the poor man was so swollen up he could not turn over in bed; and she, Sophie, stampeded around town summoning her mother and the attending physician, when Mozart took a turn for the worse. The good doctor, reluctant to leave the theater where he was watching a play, showed up after the final curtain, and prescribed cold poultices, which put his patient into a coma from which he never emerged. According to Sophie anyway.

There are several gruesome and wildly contradictory commentaries about Mozart’s last hours, delivered by witnesses, the sisters, and Süssmayr; so we have no idea what actually happened around his deathbed. Additional efforts were surely made post mortem to make these stories as heartrendingly pathetic as possible, in order to stir the hearts of patrons, publishers, fans, biographers, and other sources of future income for the widow of the great man.

When Sophie’s husband died, she moved in with Constanze, now twice widowed, and living in Salzburg. When Aloysia was also widowed, she also moved in with her two sisters, and the three kept house together until the end.